Introduction: Why This Matters

In quantum mechanics, we believe systems exist in a superposition of possible outcomes until they interact with an environment and decohere into one. But how is a specific path chosen? Standard theory says it’s probabilistic, following the Born rule (squared amplitudes = outcome frequencies). But that only answers what happens across many trials and not why a particular branch stabilizes in a single case. This is what I am most interested in understanding.

Physicist Vlatko Vedral has put forward the Emergent Quantum Wavefunction Interpretation (EQWI) (better captured in his book Decoding Reality than this lecture); which suggests that our conscious experience is simply what it feels like to be a particular quantum pattern in the universal wave. At the most fundamental level, we are not physical objects but quantum informational patterns.

Felix Finster’s Causal Fermion Systems (CFS) is a mathematical structure that shows how relations among fermionic (think the class of particles that make up matter,) states can generate spacetime. If spacetime itself emerges from quantum configurations of fermionic states, then everything within spacetime must also be patterns of quantum information. In this view, our conscious experience is not separate from physics, but the inside perspective of one of these stabilized informational patterns.

Constraints Build Structure

In practice, most models of decoherence simplify the environment to something stochastic and Markovian like a thermal bath, or random noise. This makes the equations solvable, and it gives us predictions that line up with the Born rule. But it also strips away the structure that real environments always have: correlations, memory effects, symmetries, constraints. When that structure is erased, the question of why we stabilize into a particular branch becomes unanswerable.

In CFS, the Born rule arises from the underlying geometry of quantum configurations. My view is that decoherence is filtered and guided by resonance compatibility between a system and its environment. Physicist Wojciech Zurek’s theory of Quantum Darwinism has already shown that redundancy plays a key role in decoherence.

Physics already gives us the amplitudes from unitary evolution, probabilities from the Born rule, decoherence to suppress interference, and redundancy to explain objectivity. But what it does not yet tell us is why one particular outcome is selected in each case, or how that selection becomes the lived reality of consciousness.

This is where my CIR²S framework comes in. If redundancy locks in outcomes, resonance and coherence shape which informational patterns can persist long enough to be redundantly copied in the first place. And if EQWI is right that we are informational patterns in the universal wave; then consciousness itself is what it feels like from the inside to be one of those stabilized, resonantly compatible patterns.

Toy Model

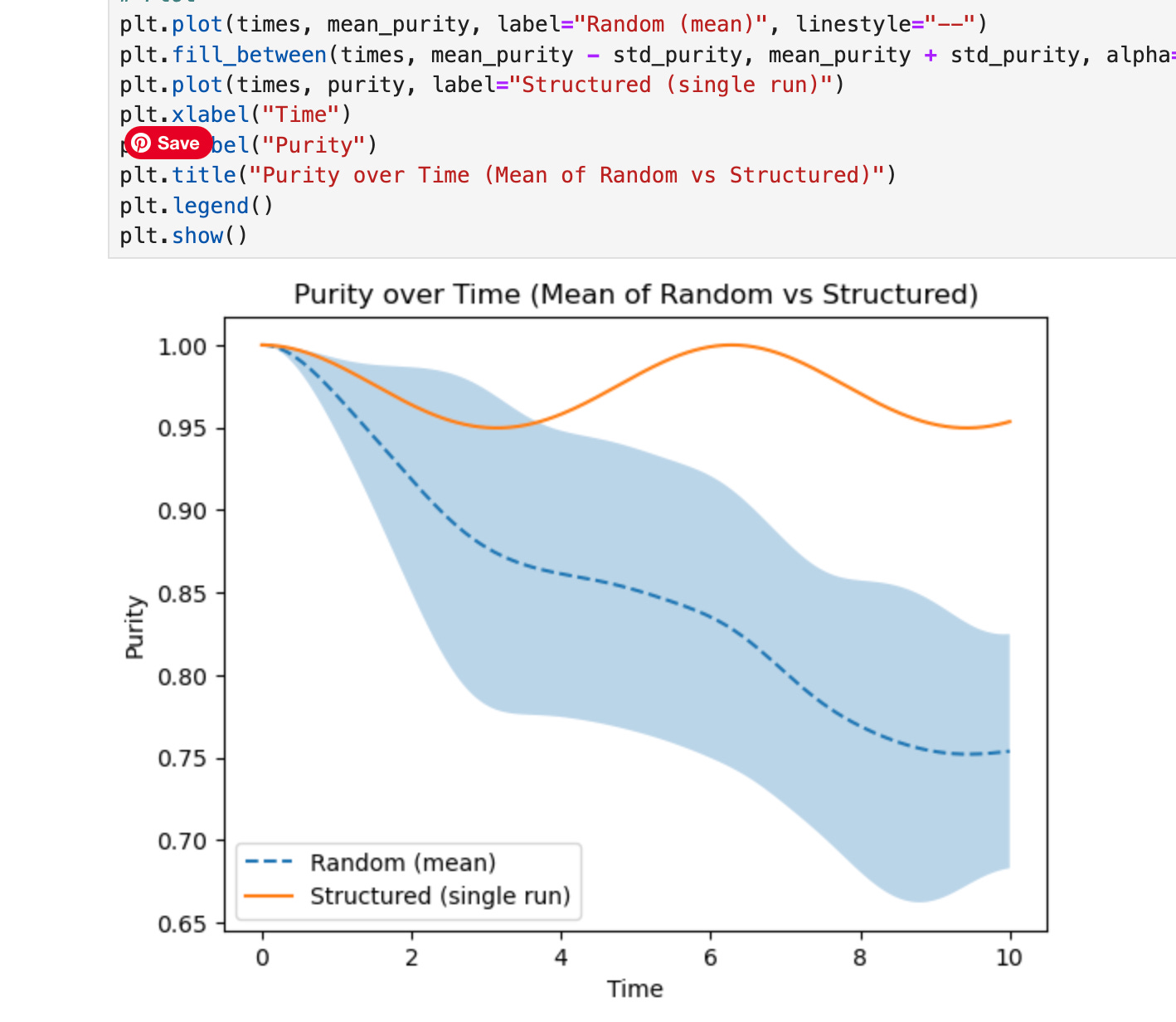

To explore this, I built a mini simulation using open-source tools. I’m not a physicist or a coder by training, but the experiment is very straightforward. The goal: test whether a structured environment leads to more stable, coherent outcomes than a random one, even when both respect the same quantum probabilities. My goal is to show how resonance and structure can shape how long something stays coherent. I contrasted two types of environments: one with structure (a coherent oscillator) and one without (a random Hermitian operator) to demonstrate what sort of difference a resonant environment can make.

What Was Simulated

The core system is a qutrit 3-level quantum state (a qubit is 2-levels) in perfect superposition. It interacts with two types of environments:

- Structured: A coherent oscillator, symmetrically coupled to the system.

- Random: A fully unstructured interaction—a random Hermitian operator with no alignment, coherence, or symmetry.

Both environments are equal in size and energy. The only variable is structure.

Using the QuTiP (Quantum Toolbox in Python), I evolved the combined system over time. I didn’t measure outcomes directly. Instead, I tracked purity, a measure of coherence. Purity near 1 means the system remains quantum. Near 0 means decoherence is complete.

What I Saw

In the structured environment:

- Purity remained high

- Decoherence was slow and oscillatory

- The system appeared to stabilize in alignment with environmental structure

In the random environment:

- Purity dropped rapidly

- Decoherence was fast, erratic, and inconsistent across trials

To rule out statistical noise, I ran 30 random-environment trials and averaged the results. The contrast held: structured coupling preserves coherence; random coupling doesn’t.

What This Suggests

This toy model supports the view that decoherence is filtered by resonance compatibility between the system and its environment!

Why the Random Case Is Artificial

The “random” environment I used was deliberately without constraints ( no conserved quantities, no phase coherence, no filtering from environmental geometry). Such an environment doesn’t exist in nature. What this toy model shows is not a contrast between “realism” and “physics,” but between natural resonance and the artificial removal of constraints. And, if you think about it, constraints around systems are what create those systems.

What’s Next

The toy model was a conceptual step. My next phase is to move into live experiments that test CIR²S more directly. I am now in the process of building Experiment 3, which alternates between live quantum random streams, pre-recorded retro sequences, and a ghost channel as a control. Each run is analyzed to see if any of the signatures CIR²S predicts are present:

- Coherence – do results persist longer than chance would predict?

- Resonance – do the bit streams show internal correlations beyond randomness?

- Redundancy – do repeated trials amplify small effects?

- Selection – does order emerge over time, revealed in entropy shifts?

This design is inspired by Helmut Schmidt’s classic random number generator (RNG) experiments from the 1970s. Schmidt tested whether human intention could bias RNG outputs, both in real-time and with pre-recorded sequences, and he reported small but consistent deviations from chance. In my framework I am also testing for psychokinetic (PK) effects. But I approach them through the lens of CIR²S. Rather than asking only whether intention can shift outcomes, I examine how any such influence might leave signatures in coherence, resonance, redundancy, and selection. In this view, PK is reframed as a subtle bias inside the same quantum processes that already stabilize outcomes.

In other words, this next experiment is where CIR²S becomes empirical. It asks: do coherence, redundancy, and selection leave measurable signatures in quantum randomness? And if so, could these be the first footholds for understanding how a probabilistic quantum world crystallizes into the particular, lived realities we experience?

Conclusion

Quantum systems don’t simply collapse according to the Born rule in isolation. They decohere within structured environments, where resonance, redundancy, and constraints filter which possibilities stabilize into reality.

EQWI tells us we are quantum informational patterns.

CFS shows how spacetime itself can emerge from relations among those patterns.

CIR²S adds the process: coherence, information, resonance, redundancy, and selection.

Consciousness is what it feels like to be one of those stabilized patterns.

If You’re Curious

- All of this was done using Python, Jupyter Notebook, and QuTiP.

- No lab needed.

- If you want to try it yourself.

Leave a Reply